beautiful

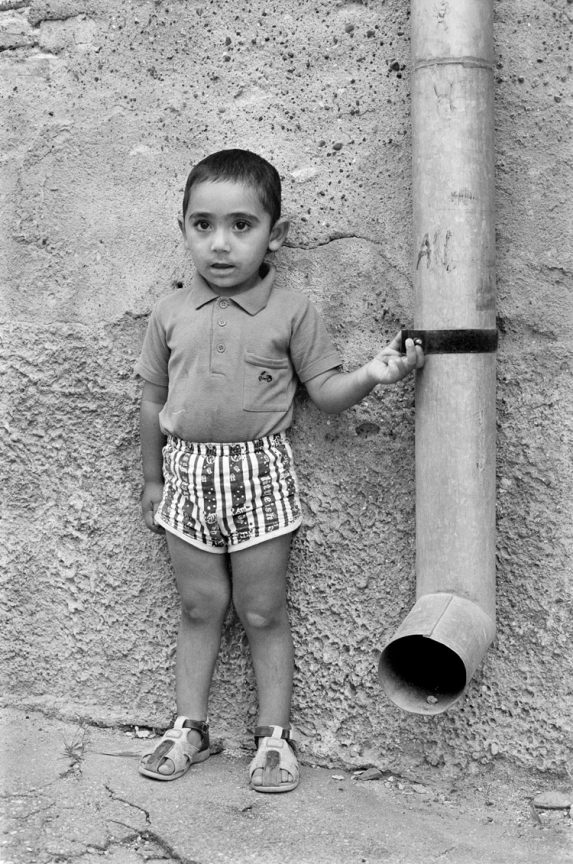

“When she’s big, she’ll be a grandmother and she’ll travel to Germany as there’s no death there. For now, though, she’s still small and the water hurts and the drain has eyes and the boiler’s wheezing. There’s no air in the bathroom and in her chest, no space, and between her temples the throbbing trembles. Soon though, soon she’ll be big.”

“She sweeps the rug. She’s sweeping it for her mother. She sweeps the sorrows away and her father back and the fringes straight. She sweeps them from right to west and becomes their ally against the big people as it’s their footsteps that make the fringes go all crooked and stick together and then nothing is as it was before.”

“Every day, she counts her gummy bears, arranged neatly by color, with legs and breasts, this time more carefully, another time more wildly. What satisfaction she then feels! What bliss at every single one! And once she decides, upon mature reflection, that on a day like today only the palest one should go into her mouth, she places him expectantly on her alert tongue, rolls him gently along the curve of her palate, tempts him into the depths of her gullet until he freely surrenders his much-traveled flavor. Then she licks his back, sucks the paleness from his cheeks, sucks him thin, fills her mouth and the day with him, the chosen one. And when evening comes, it brings with it the calming certainty that far more garish treasures have been reserved for the next seven days. Later, many years later, she checks her bank balance, day after day. The more money she finds there, the happier she is. In the mornings, she often goes online and looks at the numbers and a seven makes her feel tranquil and free.”

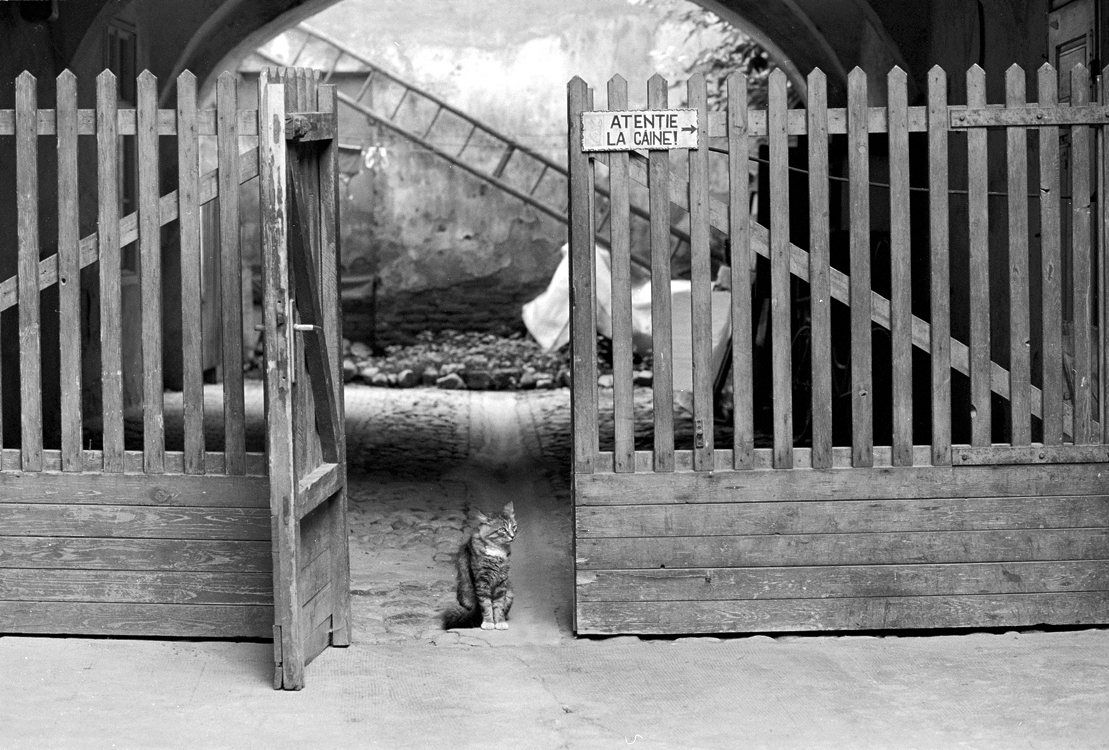

“They leave. Finally, they leave the land of their roots for the land where their language is spoken. There are many of them, older ones, younger ones, the very small ones on knees. And they go to the land they dreamt of, with their belongings and the right to, and without their mother’s mother’s mother as she is old and wants to die where she remembers, on ground her feet know well. She remains behind, and the state gives space in her apartment to a family she doesn’t know, a mother and father and small child. And the child builds a ship out of two chairs and an umbrella and she sails with it to Africa and on the way they eat carrots that the child enjoys more once her crooked fingers peel sweetness into them. And because she’s very old, she is small again, but that suits them fine. And so they often go for a walk and the one who is a little bigger has her hand on the head of her little friend who stops when she feels the hand tiring as they’re not in a rush. For a long time now, her back has been curved, bent by a lot of living. You could call it a hunchback, but it is the curve of affection that brings the old face closer to the young one, a closeness known by very few at this time.”

“She comes home from school. She hates school as the school hates boys and teaches only girls. She plays this hatred away and then starts bleeding. Why is she bleeding? She washes off the blood and her legs and puts on clean pants, top and bottom. She waits and is afraid for she is bleeding again and understands nothing anymore. She washes off the blood and her legs and puts on clean pants, top and bottom. She waits again and is more afraid for the blood is bleeding again, down her legs. Die, she’ll die, she’ll die soon for sure, and Germany’s to blame for everything, this boy-free Germany, where she had to go and knew nothing, and now nothing is as it once was.”

Texts by Loredana Nemes (translated by Donal McLaughlin, 2013)